Michael Huemer is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Colorado at Boulder and is the author of the book The Problem of Political Authority: An Examination of the Right to Coerce and the Duty to Obey. The following is the response he sent me addressing the question I asked him in a previous email: How Bad Would Anarchy Have to Be to Justify Unjust Government Activity?

Your question is an instance of the broader question: “How large must the benefits be to justify a rights violation?” (For instance, for what number n is it permissible to kill one innocent person to save n innocent lives?) One extreme answer is “Rights violations are never justified,” but for various reasons, I think this answer [is] indefensible. Another extreme answer is consequentialism, “Rights violations are justified whenever the benefits exceed the harms” – which is really equivalent to saying there are no such things as rights. This is not indefensible, but it is very counter-intuitive. So we’re left with a seemingly arbitrary line somewhere in the middle. Obviously, no one knows precisely where the line is. Fortunately, we also don’t need to answer that question to choose a political philosophy.

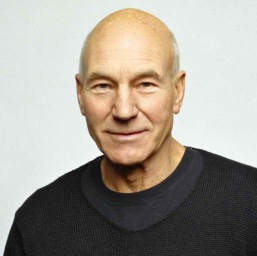

Patrick Stewart

Analogously, you don’t need to answer “exactly how many hairs must a person have on their head in order to not count as ‘bald’?”, in order to say whether Patrick Stewart is bald, because Patrick Stewart is nowhere near the borderline; he’s deep into “bald” territory. If you have a 2000-pound pile of sand in your back yard, you don’t need to answer “exactly how many grains of sand make a heap?” in order to know that you have a heap in your back yard.

Similarly, we don’t need to answer “How Bad Would Anarchy Have to Be to Justify Unjust Government Activity?” because our predictions for how bad – or rather, how good – anarchy would be are just going to be nowhere close to the line. We’re nowhere close to the case where government would be justified.

Now, I did not discuss roads or schools in my book, as you (and another reviewer) mentioned. That is because the book was already at the word limit, there are about two dozen other things that someone thinks I should have put in, and they couldn’t all go in. (For example, should I have deleted the chapter on national defense, so I could talk about roads?). However, there’s really no reason to think that roads or schools in the anarchist society would be worse than in a governmental society.

The argument from schools strikes me as particularly lame. I think it’s mainly professional educators, who are worried about losing their huge government subsidies, who are worried about this. If you learn that your next door neighbor isn’t sending his kids to school, would you be justified in kidnapping the kids to force them to go to a school run by you?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

This is the third of three related blog posts featuring discussion between Prof. Mike Huemer and I. All three posts deal with the question of when it is moral to support or commit aggression:

(1) Morally Permissible Unjust Acts: Defending the Rights-Based Approach to Defending Libertarianism

(2) How Bad Would Anarchy Have to be to Justify Unjust Government Activity?

(3) Mike Huemer: “We’re nowhere close to the case where government would be justified.”

August 13, 2013 at 6:44 pm

Interesting response. He states that there are two extremes – “its never ok to violate rights” and ” its ok in some situations to violate rights”. As I pointed out before, and he points out in his response, the latter would result in there effectively being no rights at all.

He claims the answer lies somewhere in the middle. My thought here is there is no middle ground. Any line drawn between the idea that “rights exist and its never moral to violate them” on one side and “sometimes its ok to violate rights” on the other, equates to suggesting that some scenario exists that would justify violating individual rights. Unless the line is drawn at at the extreme position that it is never moral to violate rights, we are saying that in some cases it is ok. This brings us right back to the conclusion rights don’t exist – that rights are not unalienable but rather predicated on environmental factors. A system of rights based on environmental factors is no rights at all. If rights can come and go they cease to be what they have historically been. If you change something it is not the same. That’s why we both conclude that either rights exist and it is never moral to violate them or it is moral to violate in some cases which renders the whole idea of rights useless.

You and he both keep referring to a hypothetical situation where wrong can supposedly be justified based on some alleged mass benefit. This seems odd to me. I cant fathom such a scenario. First the idea of benefitting from some imorral action is entirely subjective. There is no way to determine quantitatively if ones supposed benefit is sufficient enought to justify doing harm. There is no unit of benefit. Second benefit is entirely individual. If you talk of societal benefit you are simply referring to the level of benefit each individual in society alleges to potentially stand to gain. You cannot add my benefits to yours because 5 units of benefit for me has no correllation to units of benefit to you. Benefit is subjective. It cannot be quantified in any meaningful way.

If I take what you are suggesting and change the scenario from a million people benefitting to just one person, it becomes a bit easier to see how dangerous a proposition it is to imagine that the benefit can morally justify aggression. Just because I may benefit if I steel your car, it can never be that my benefit justifies theft. If that were the case all theft would be justified. The same goes for any type of aggression. If the benefit of violating someones rights makes it ok nothing is immoral.

August 13, 2013 at 10:16 pm

Hello again onesquarelight. Thanks for all of your comments–it’s nice to discuss this subject with multiple people so I can hear more perspectives on it.

You misunderstood what Huemer said. He worded the second extreme answer as follows: “Rights violations are justified whenever the benefits exceed the harms.”

If he had said that the second extreme answer is that “its ok in some situations to violate rights” (your words), then you would be correct that there is no middle ground.

But there is a middle ground when the second extreme answer is: “Rights violations are justified whenever the benefits exceed the harms.”

For example, one could answer that “Rights violations are justified whenever the benefits substantially exceed the harms.”

To explain this all using the “bald” analogy:

How little hair must a person have on his head for him to be bald? One extreme answer is to say that he must have absolutely no hair on his head in order to be considered bald. By this definition Patrick Stewart is not bald, since he has some hair (see the picture of him in the blog post).

Another extreme answer would be to say that everything from no hair to a receding hairline counts as bald. Yet we don’t accept this definition either since we don’t consider people with receding hairlines as “bald.” Perhaps we would say that they are “going bald,” but we definitely wouldn’t say that they are bald already.

(Note that the analogous misinterpretation of the second extreme answer is that “people with some hair are bald.” There is indeed no middle ground between the definitions of “bald” as “no hair” and “bald” as “some hair.”)

Our answer is thus somewhere in the middle. If a person has a sufficiently small amount of hair on their head then we call them “bald.” (Note that merely having a receding hairline is not a sufficiently small amount of hair to be considered “bald.”)

Similarly, Huemer and I’s middle answer is that if the benefits of committing a rights violation exceed the harms of committing the rights violation by a sufficient margin/factor then (Huemer and I believe) the rights violation is morally justified.

You claim that “[If] it is moral to violate [rights] in some cases [then] the whole idea of rights useless.”

I disagree with this claim for several reasons. First, even if the concept of rights would be useless to questions of morality, the concepts of rights would still be useful to questions of what the law should be. Second, the concept of rights are in fact still useful to the question of morality:

Instead of saying “it’s always immoral to violate rights” as you are saying, Huemer are just saying “it’s immoral to violate rights unless the benefits of doing so substantially exceed the harms.” In both cases the concept of rights is still useful to questions of morality. In the first case, if someone asks “Was it immoral for him to do X?” you would answer “Yes, because X is a rights violation.” In the second Huemer and I would answer, “Yes, because it is a rights violation and because the benefits of him doing X did not exceed the harms of doing X by a sufficient amount.” Note that the “because it’s a rights violation” part of Huemer and I’s answer was a necessary inclusion since saying “the benefits of him doing X did not exceed the harms of doing X by a sufficient amount” is not a sufficient reason for an action to be immoral. Therefore, the concept of rights is still useful to questions of morality, even if you adopt the view (as Huemer and I do) that violating rights is not always immoral.

“You and he both keep referring to a hypothetical situation where wrong can supposedly be justified based on some alleged mass benefit. This seems odd to me. I cant fathom such a scenario.”

Oh no, I apologize! My last three (3!) blog posts have been on this subject of rights-violations sometimes being justified. This is my third blog post of the three. The second was the one you were commenting on previously: “How Bad Would Anarchy Have to Be to Justifiy Unjust Government Activity?” The first blog post, which I failed to link to in the second blog post (I’m sorry, forgive me!–I’ll change that now) is titled “Morally Permissible Unjust Acts” ( https://peacerequiresanarchy.wordpress.com/2013/08/04/morally-permissible-unjust-acts/ ).

To summarize the content of my blog post “Morally Permissible Unjust Acts” briefly (although I’ll hope you’ll give it a read), Huemer gave a presentation in which he pointed out that there are some scenarios in which a large majority of people would agree that you should violate peoples’ rights. During the presentation he asked his audience, “Is it permissible to violate the person’s rights in this scenario?” The libertarian audience seemed to have a lot they wanted to say about how unfair the question was, but nobody voiced the objection that I had, namely that there are two distinct questions we should be asking: (1) Is it morally permissible to violate a person’s right in X scenario?” and (2) “Should it be illegal to violate that person’s right in X scenario?” Huemer seemed to believe that in the cases where it was morally permissible to violate someone’s right it should also be legal to do so. I disagreed and hence sent him my first email (featured in the blog post) in which I argued that there are “morally permissible unjust acts”–i.e. acts that are morally justified but that should still be illegal since they are rights violations. For examples of what some of these scenarios are in which Huemer and I and most people agree that it is morally permissible to commit rights violations, please see the post “Morally Permissible Unjust Acts”: https://peacerequiresanarchy.wordpress.com/2013/08/04/morally-permissible-unjust-acts/ Peace. Thanks again for the discussion.

August 15, 2013 at 12:21 pm

I’ve read you posts and your comments. I’ve even read some of the comments at the Ron Paul Forum. Your premise that it’s moral to steel is bogus. It’s nothing more than moral relativism. I don’t buy it. I am a moral absolutist. The analogy of the cabin in woods is a good one but you’ve only taken it far enough to make your point seem valid.

“The whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.“ ~Hazlitt

Theft is never moral. You continue to say that it is. I assure you it is not. Violating the rights of another is never morally justifiable.

This whole cabin analogy is nothing more than a variation of the “Broken Window Fallacy”. The benefactor of aggression is the only person you’ve focused on. You’ve not examined the harm that may come to the property owner as a result of the vandal/thief that you want so desperately to prove is acting morally. Far from being a “common sense approach to liberty” it is mindless drivel and void of all logic. There is no backdoor to truth. There is no point at which immoral becomes moral. This guy you’re talking with is leading you astray. You need to read Murray Rothbard’s “Ethics of Liberty” and Henry Hazlitt’s “Economics in One Lesson”. Both can be found for free online.

Also, here is a related article that you might bring some clarity. http://mises.org/daily/2968

August 15, 2013 at 7:39 pm

“Your premise that it’s moral to steel is bogus.”

That’s not my premise.

“It’s nothing more than moral relativism.”

I’m not a moral relativist.

“I don’t buy it.”

I think that’s most likely because you’re still confused about what my position is.

“I am a moral absolutist.”

I’m not (nor is Prof. Huemer), at least in regards to being a moral absolutist in regards to theft. Moral absolutism completely contradicts most peoples’ moral intuitions including my own. Very few people would agree with you that it is always wrong to commit theft. If you asked a bunch of people “Is it always wrong to commit theft?” you might find a fair number of people who would say yes, but if you presented them with hypothetical scenarios in which committing a minor act of theft was the only way to avoid some very disastrous outcome, then most people would say that morally the right thing to do would be to commit the act of theft.

“The analogy of the cabin in woods is a good one but you’ve only taken it far enough to make your point seem valid.”

What do you mean by this? Also note that the cabin-in-the-woods scenario is not an analogy. You may want to look up what that word means. It’s not being compared to any other scenario.

“The whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate hut at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.“ ~Hazlitt

Oh, now I see what you meant by “you’ve only taken it far enough to make your point seem valid.”:

You’re claiming that the reason why my moral intuition tells me that it’s permissible for the starving person lost in the woods to break into the cabin and steal food is because I’ve failed to notice that the cabin/food owner is harmed when the starving person trespasses and steals his food. Well your claim is false: I’m fully aware of the fact that the owner of the food is harmed when his food is stolen. I’m not ignoring this fact. Rather, I’m claiming that this harm to the cabin/food owner is sufficiently small relative to the harm (death) that the starving person faces if he does not commit the act of theft that it is morally permissible for the starving person to commit the act of theft.

“Theft is never moral. You continue to say that it is. I assure you it is not. Violating the rights of another is never morally justifiable.”

This isn’t persuasive at all.

“This whole cabin analogy is nothing more than a variation of the “Broken Window Fallacy”. The benefactor of aggression is the only person you’ve focused on. You’ve not examined the harm that may come to the property owner as a result of the vandal/thief that you want so desperately to prove is acting morally.”

No it’s not. As I said above, I’m fully aware of all the harms and benefits in the scenario. I’m not denying that the cabin owner is harmed.

“Far from being a “common sense approach to liberty” it is mindless drivel and void of all logic.”

Huh? In his book “The Problem of Political Authority” Huemer argues for anarcho-capitalism from “common sense” moral premises, i.e. relatively uncontroversial moral beliefs that a great majority of people presumably accept. I’m not sure what you’re trying to critique. His approach is not “mindless drivel.”

“There is no backdoor to truth.”

There’s no need for rhetoric.

“There is no point at which immoral becomes moral.”

What do you mean? Do you mean to say that actions, such as theft, that are typically immoral can never be moral even if the benefits of the actions outweigh the harm by a tremendous factor and margin? If so, I disagree.

“This guy you’re talking with is leading you astray.”

You’re joking, right? When you first became libertarian and were discussing your political views with your statist friends, how would you have reacted if they had said “This Murray Rothbard guy you’re reading is leading you astray”? Of course you would have said, “That’s not an argument. If you disagree with libertarianism, give me a reason to reject it and I’ll consider what you say rationally.” When you say that Prof. Michael Huemer is leading me astray you remind me of the statists in my life. Please try appealing to reason rather than make meaningless “This guy you’re talking with is leading you astray”-type comments. Thanks.

“You need to read Murray Rothbard’s “Ethics of Liberty” and Henry Hazlitt’s “Economics in One Lesson”. Both can be found for free online.”

I have only read parts of Rothbard’s “Ethics of Liberty.” However, I have read Rothbard’s “For a New Liberty” along with many essays by Rothbard, so I’m quite aware of his absolutist rights-based approach to libertarianism. My blog post on Rothbard’s “For a New Liberty” ( https://peacerequiresanarchy.wordpress.com/2013/01/02/for-a-new-liberty-murray-rothbard/ ) contains a section in which I discuss “Natural Rights vs. Consequentialism” that you may find interesting.

I have read Henry Hazlitt’s “Economics in One Lesson.” See my blog post on it here: https://peacerequiresanarchy.wordpress.com/2012/06/29/henry-hazlitts-economics-in-one-lesson/ Note that Hazlitt was a consequentialist to a degree (like Huemer and I and the vast majority of people, but unlike you).

Rothbard, in the paper you linked to on Mises wrote:

“What I have been trying to say is that Mises’s utilitarian, relativist approach to ethics is not nearly enough to establish a full case for liberty. It must be supplemented by an absolutist ethic — an ethic of liberty, as well as of other values needed for the health and development of the individual — grounded on natural law, i.e., discovery of the laws of man’s nature.”

To clarify, I’m not a utilitarian (and I’m not sure that Rothbard is right to say that Mises was). However, I do still disagree with Rothbard on “natural rights” being some sort of moral fact of nature. They’re not. That’s a myth. I’m an emotivist. See my discussion of this subject in the “Natural Rights vs. Consequentialism” section of my blog post on “For a New Liberty”: https://peacerequiresanarchy.wordpress.com/2013/01/02/for-a-new-liberty-murray-rothbard/

August 15, 2013 at 10:02 pm

You are justifying theft. That is your premise. You believe that in some situations theft is moral. You are not a moral absolutist from my perspective. It is my opinion that you contradict yourself a lot and don’t seem to know it. Perhaps I should have used the term parable rather than analogy.

I’m going to try this again.

Theft is perpetrated when a person is denied the right to determine how or if their property is utilized. Theft benefits the theif and injures the owner. The amount to which the thief benefits is entirely subjective. The amount which the owner suffers is entirely subjective. There is no standard unit of benefit. There is no standard unit of suffering. There is no way, other than to use your own personal subjective valuation, to claim that a thief benefits sufficiently and the owner is injured minimally enough to magically make theft moral. You cannot state that the thief benefited by 100 benefiticos and the owner suffered only 3 suffericos and arrive at some mathematical equation to determine the point at which theft is or is not moral.

The owner is injured to the extent he determines. The thief benefits to the extent he determines. A thief may decide that the risk is worth the possible negative outcomes of enguaging in theft, but he cannot decide that what he is doing is not steeling. No. He must calculate the risk and accept the reprocussions of his choice.

Suppose the man has his cabin rigged to fire a gun when the door is opened and thief is killed. Suppose the cabin has only a small amount of food and the owner has been living on only a few bites of food a day because he has not had a successful hunt in weeks. Suppose the thief eats the only food he has left and when he returns from another unsuccessful hunt he himself is near starvation. Suppose he dies as a result of being robbed. Suppose the thief breaks the window and it is the middle of winter and the owner dies from exposure because he doesn’t have another window. Suppose the thief is cold so he burns up all the owners firewood and when the owner returns ha has suffered an injury and cannot gather more wood and dies.

The simple point is that one mans need does not alter moral foundation of property rights. There is simply no means of determining a ratio of benefit to harm when dealing with the subjective nature of value. The owners right to utilize his property to sustain life as he sees fit is not up for a vote. Just because 10 people decide that the starving man should steel and only 1 says he cannot matters none because the 1 is the owner. The decision is his and his alone. Property rights are not democratically controlled. Your own personal moral valuation of the matter cannot alter the fact that you have no authority to permit a man to steel from another. You cannot grant authority that you do not possess. Ones opinion on the matter of whether it is right or wrong to steal has no effect on the underlying morality or immorality of the act. Steeling is either immoral or it is not. A moral absolutist denies that certain conditions can alter what is and is not moral.

Your argument is not that far removed from what I hear coming from the liberal democrat. We are told that government knows better how to allocate resources than property owners and this is justification for taxation. We are told that the poor benefit more than the rich suffer so it is morally right to steel from the rich and give to the poor. We are told that the state can provide protection from danger so it is necessary for the common benefit of the masses to confiscate or limit what people may own to protect themselves.

Obamacare is argued on exactly the same premise that you present with the cabin story.

August 15, 2013 at 11:03 pm

“You believe that in some situations theft is moral.”

Right.

“Theft is perpetrated when a person is denied the right to determine how or if their property is utilized. Theft benefits the theif and injures the owner. The amount to which the thief benefits is entirely subjective. The amount which the owner suffers is entirely subjective. There is no standard unit of benefit. There is no standard unit of suffering. There is no way, other than to use your own personal subjective valuation, to claim that a thief benefits sufficiently and the owner is injured minimally enough to magically make theft moral. You cannot state that the thief benefited by 100 benefiticos and the owner suffered only 3 suffericos and arrive at some mathematical equation to determine the point at which theft is or is not moral.”

I agree.

“[The thief must] accept the repercussions of his choice.”

I agree: I think it should be illegal for the starving person to steal the food.

“Suppose the cabin has only a small amount of food and the owner has been living on only a few bites of food a day because he has not had a successful hunt in weeks. Suppose the thief eats the only food he has left and when he returns from another unsuccessful hunt he himself is near starvation. Suppose he dies as a result of being robbed. Suppose the thief breaks the window and it is the middle of winter and the owner dies from exposure because he doesn’t have another window. Suppose the thief is cold so he burns up all the owners firewood and when the owner returns ha has suffered an injury and cannot gather more wood and dies.”

Then it would be immoral to commit the act of theft. But you’re fighting the hypothetical. Don’t. Suppose that there are obvious signs that the cabin has not been used in several weeks. Suppose that when the starving person breaks in he finds cobwebs and dust over large piles of food. Suppose that he knows beyond a reasonable doubt that by stealing some of the food he will not cause the owner of the food or anyone else to have too little food to live. Supposing all of this were true, would it be morally permissible for him to save his life by stealing some of the food and eating it? My answer is a confident yes.

“The simple point is that one mans need does not alter moral foundation of property rights. There is simply no means of determining a ratio of benefit to harm when dealing with the subjective nature of value. The owners right to utilize his property to sustain life as he sees fit is not up for a vote. Just because 10 people decide that the starving man should steel and only 1 says he cannot matters none because the 1 is the owner. The decision is his and his alone. Property rights are not democratically controlled. Your own personal moral valuation of the matter cannot alter the fact that you have no authority to permit a man to steel from another. You cannot grant authority that you do not possess. Ones opinion on the matter of whether it is right or wrong to steal has no effect on the underlying morality or immorality of the act. Steeling is either immoral or it is not. A moral absolutist denies that certain conditions can alter what is and is not moral.”

You’re attacking a straw man. How many times must I repeat my position before you understand it? As I’ve said countless times, I agree with you that the cabin owner should have the legal right to his food. I agree that “Property rights are not democratically controlled. Your own personal moral valuation of the matter cannot alter the fact that you have no authority to permit a man to steel from another. You cannot grant authority that you do not possess.” I agree. I agree. I agree.

“Steeling is either immoral or it is not.”

Why do you keep saying this nonsense? There are obviously three possibilities: Either stealing is always immoral, sometimes immoral, or never immoral. You could also say “stealing is either always immoral or it is not always immoral” (maybe this is what you meant above?) but again, this is very obvious so there’s no need for you to keep saying it. I get it.

“Your argument is not that far removed from what I hear coming from the liberal democrat. We are told that government knows better how to allocate resources than property owners and this is justification for taxation. We are told that the poor benefit more than the rich suffer so it is morally right to steel from the rich and give to the poor. We are told that the state can provide protection from danger so it is necessary for the common benefit of the masses to confiscate or limit what people may own to protect themselves. Obamacare is argued on exactly the same premise that you present with the cabin story.”

No. Not at all.

Okay, this is getting pretty ridiculous. I’m going to pose one more hypothetical scenario–don’t fight it–and see whether you agree with the vast majority of people and I that it is morally permissible to commit an act of theft. If you don’t agree that it is morally permissible to commit the act of theft in this very extreme scenario, then it’s probably true that you are going to stubbornly hold onto your ideological belief that it is always immoral to commit theft no matter what else I say and we probably should stop talking about this point. Here is the argument. Is it valid? Are the premises true? If not, which do you disagree with?

(1) People should never do things (perform acts) which are immoral.

(2) Every act that is not immoral is morally permissible.

(3) If there is an asteroid flying at the earth that is going to kill a billion people five minutes from now unless you steal my shoe and throw it at the asteroid (in which case the asteroid will be deflected back into space sparing the billion peoples’ lives), you should steal my shoe and throw it at the asteroid.

(4) Therefore, it is morally permissible to steal my shoe and throw it at the asteroid to save the billion peoples’ lives.

August 16, 2013 at 11:39 am

Thank you for posting. I’m not a Moral Intuitionist, but I given overlap between correct moral philosophy and correct moral philosophy, the implications Huemer draws are really important. Plus, since common sense is considered whatever is popularly agreed upon, his defense of libertarianism from common sense ought to be very effective rhetorically almost by definition.

How bad would Anarchy have to be? It seems that morality is nothing if not universal. It is the greatest good, to be pursued at all costs. Of course, what that good is is the crux of the matter.

Its very cool that Michael Huemer responded to you. I was ecstatic when Bryan Caplan just signed by book!

August 16, 2013 at 12:28 pm

I think morality has more to do with the reaction of the victim than it has to do with the thief. I’m certain that the thief has acted immorally because theft is immoral. But that being the case, the owner would be acting immorally to deny a dying man aid if it was within his power to do so. If a man trespassed, vandalized, and stole from me, but I was made aware of the condition under which he did this was a matter of life and death, I would be morally obligated to forgive. My moral duty to forgive a hungry thief does not make the theft moral (which has been what you’re trying to prove).

August 16, 2013 at 12:33 pm

“It seems that morality is nothing if not universal.” Well said Eli.

August 16, 2013 at 2:37 pm

onesquarelight, may you clarify whether or not you agree with the following?:

“If there is an asteroid flying at the earth that is going to kill a billion people five minutes from now unless you steal my shoe and throw it at the asteroid (in which case the asteroid will be deflected back into space sparing the billion peoples’ lives), you should steal my shoe and throw it at the asteroid to save the billion peoples’ lives.”

Presumably the vast majority of people agree with the above. However, since you say you believe that theft is always immoral then it seems that in order to stay consistent you must disagree with the above by saying that you should *not* steal my shoe to save the billion people from being killed by the asteroid. This is an extraordinarily extreme view in my opinion. Is it really your position?

August 16, 2013 at 2:59 pm

Eli,

Thank you again for the recommendation to read Huemer’s book “The Problem of Political Authority”! I really am glad you told me about it. I recently bought it and just read the first three chapters yesterday. It is fantastic! I will definitely be sharing it with others — libertarians and non-libertarians alike.

I do not think that I am a “moral intuitionist” either. Rather, I think I am an “emotivist.” Note that I haven’t read any of the literature on either of these two terms, so I may be mistaken about what each of them mean and may consequently not actually be best described as an “emotivist.” My understandings of the terms come from Wikipedia:

“At minimum, ethical intuitionism is the thesis that our intuitive awareness of value, or intuitive knowledge of evaluative facts, forms the foundation of our ethical knowledge. The view is at its core a foundationalism about moral beliefs: it is the view that some moral truths can be known non-inferentially (i.e., known without one needing to infer them from other truths one believes).” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethical_intuitionism )

This sounds almost like what I believe (in that I arrive at my moral beliefs intuitively rather than deriving them from other beliefs using arguments), except that I’m not sure that there is in fact “ethical knowledge” at all. Wikipedia goes on to say this about moral intuitionism:

“Such an epistemological view implies that there are moral beliefs with propositional contents; so it implies cognitivism.” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethical_intuitionism )

Note that “Cognitivism is the meta-ethical view that ethical sentences express propositions and can therefore be true or false (they are truth-apt), which noncognitivists deny.” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitivism_(ethics) )

I disagree with this. I see no reason and have no evidence to believe that sentences such as “murder is always wrong” or “murder is not always wrong” are “true” or “false.” I think I’m a noncognitivist:

“Non-cognitivism entails that non-cognitive attitudes underlie moral discourse and this discourse therefore consists of non-declarative speech acts, although accepting that its surface features may consistently and efficiently work as if moral discourse were cognitive. The point of interpreting moral claims as non-declarative speech acts is to explain what moral claims mean if they are neither true nor false (as philosophies such as logical positivism entail). Utterances like “Boo to killing!” and “Don’t kill” are not candidates for truth or falsity, but have non-cognitive meaning.” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-cognitivism )

And as I said before, I think I am an emotivist:

“Emotivism, associated with A. J. Ayer, the Vienna Circle and C. L. Stevenson, suggests that ethical sentences are primarily emotional expressions of one’s own attitudes and are intended to influence the actions of the listener. Under this view, “Killing is wrong” is translated as “Killing, boo!” or “I disapprove of killing.”” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-cognitivism )

“Emotivism is a meta-ethical view that claims that ethical sentences do not express propositions but emotional attitudes.” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emotivism )

August 16, 2013 at 7:50 pm

If there is an asteroid flying at the earth that is going to kill a billion people five minutes from now unless you steal my shoe and throw it at the asteroid (in which case the asteroid will be deflected back into space sparing the billion peoples’ lives), you should steal my shoe and throw it at the asteroid to save the billion peoples’ lives.”

Property can be used toward immoral ends. Your shoe is your property but that doesn’t mean that you can morally do anything you want with it. For you to refuse to utilize your property in a manor which you know can save your own life as well as a billion others would be immoral. Any attempt to take your shoe would be an act of self-defense, not theft, and therefore quite moral.

August 16, 2013 at 8:54 pm

“Any attempt to take your shoe would be an act of self-defense, not theft, and therefore quite moral.”

No, it’s theft. If I explicitly tell you that you do not have my permission to use my property and yet you ignore me and use it anyway then you are guilty of theft. You have the right to defend yourself, of course, but you don’t have the right to use other peoples’ property without their consent to defend yourself, unless of course they are participating in the attack against you. I’m not participating in the asteroid’s attack against you though. I’m merely refraining from helping you to stop it. Therefore, it would indeed be theft for you to take my shoe.

Another analogous scenario: Suppose you are standing in the street outside my house. A fast madman with a machete starts running at you trying to kill you. You have no weapon to use to defend yourself and you know you won’t be able to outrun the madman for long so you run down my driveway into my house in the hope that you can reach my kitchen and grab a knife for defense before the madman catches up to you. By breaking into my house and taking my knife and using it without my permission you are committing theft. It’s also true that you are acting in self defense when you use the knife to defend yourself from the madman, but this doesn’t change the fact that it’s still theft for you to take my knife if I don’t consent to allow you to use it.

It’s the same in the asteroid scenario: using my shoe against my will is theft just as using the knife in my kitchen against my will is theft. You’re right about this: “For you to refuse to utilize your property in a manor which you know can save your own life as well as a billion others would be immoral.” But the fact that my choice to refuse to allow you to use my shoe is an immoral choice does not change the fact that I made the choice and you thus do not have my consent to use my shoe meaning that if you forcibly take my shoe from me against my will then you have violated my property rights — you have committed theft.

August 16, 2013 at 10:41 pm

By insisting that you are going to keep your shoe thereby willfully killing yourself and a billion other people, you are something akin to a suicide bomber. Just because the bomber owns the bomb doesn’t mean its moral for him to blow it up wherever he pleases. Anyone who is privy to his plan could justly employ force to stop him from causing them bodily harm. Your shoe is something like a key that can turn off a bomb that is set to go off in 5 minutes. The shoe is your property but your failure to utilize it to save yourself and others is an act of aggression. Since it would be you who initiated the threat of violence, all defensively action would be morally justified. Wrangling a bomb from a suicide bomber is not theft for exactly the same reason that taking your shoe to save lives is not.

August 16, 2013 at 11:06 pm

To keep these scenarios on par with one another the socond one, with the knife, would have to be set up so that you know that denying me the use of your knife will more than likely result in my death. It would be your right to deny me its use but it would be immoral. To knowingly withhold property when it can be utilized to save a life is an act of aggression as sure as the man who is chasing me. All.proportional force on my part to save my life and defend myself against aggression is moral behavior.

If you were not home, as is the case with the cabin, my only option would be to break in and use your knife without your permission. That would not be moral but it would be moral for you to forgive my tresspass given the situation I found myself in. It would be within your rights to not forgive me and even report my actions to whomever provides dispute resolution but it would not be moral. It would also not be moral for me to not fix or pay for any damage I did to your property. Of course the man with the machete probably did some damage too. That would be a proper use of the courts to recover damaged property from the dead machete wielding lunatics estate if possible.

August 16, 2013 at 11:28 pm

Here is one for you. You are on your boat. You have a life vest on board that is not currently being used. You see a person drowning near your boat. Is it an act of aggression to choose to not throw the drowning person your vest?

August 17, 2013 at 12:08 am

It’s amazing that rather than give up your belief that rights violations are always immoral you are persuading yourself that the rights violations you think it is morally permissible to commit aren’t actually rights violations.

“To knowingly withhold property when it can be utilized to save a life is an act of aggression as sure as the man who is chasing me.”

This is completely and obviously false. Nobody has any positive political obligations to protect you unless they contractually obligate themselves to protect you — if they never entered into a contract with you then they have the right to refrain from protecting you.

Maybe if I modify the scenario slightly so it’s not my knife that’s needed, but my house, you’ll understand:

Suppose you’re walking down the street when suddenly a vicious human-attacking animal jumps out of the woods. It looks like it is going to attack you so you run for the nearest house for shelter. (Note: it’s not your house.) You knock frantically on the door and the owner answers it. You ask him to let you in so that this vicious animal doesn’t eat you. However, he says, “Sorry, I know it’s immoral for me not to help you, but I’m not going to let you into my house just to illustrate a point. Bye.” The owner closes the door. Terrified, you try running to the next house to get help but before you can go more than a few steps the animal catches you and bites off your leg. The animal eats your leg and then runs back into the woods. The owner of the house who was watching the whole attack through his window opens the door again now that the animal is gone. “How are you?” he asks. You reply, “Not good. You violated my rights.” The man replies, “Oh really, which rights of yours did I violate?”

Please explain. (Or concede that he didn’t actually violate your rights.)

“Here is one for you. You are on your boat. You have a life vest on board that is not currently being used. You see a person drowning near your boat. Is it an act of aggression to choose to not throw the drowning person your vest?”

No, of course not. What rights would you allege the person violates if they refrain from saving the person? It’s just as much within your rights to refrain from giving your life vests to drowning people (provided that you are not responsible for putting them in the water) as it is within your rights to refrain from giving any of your money to charity organizations that feed starving people so they don’t die (provided that you are not responsible for depriving these people of food).

Your scenario is similar to the classic scenario in which you are walking by a lake when you see someone drowning. Nearly everyone agrees that you are morally obligated to swim out and save the person (provided that their is not a substantial risk of dying yourself). But, while we would morally condemn someone who stood by and did nothing as the person drowned, would it be justified to punish this person with force? If the family of the person who drowned sued him for failing to act and demanded restitution, should they have a case? No, because he didn’t violate anyone’s rights. He doesn’t owe any restitution to the person who drowned since he’s not responsible that the person drowned. The fact that he could have prevented it doesn’t make him responsible. There are many harms to people you could prevent, but the fact that you don’t prevent them doesn’t make you an aggressor.

August 17, 2013 at 7:37 am

Its a violation of the right to life when one is present in a life or death situation and has the resources to save a life but chooses to do nothing. Not opening your door and allowing me to use your home as temporary shelter when you know that the potential exists that I may lose my life is participating in my demise. In such a situation I am faced with two threats – the animal – directly and you – indirectly.

If I succeed in escaping death it will be because I was able to overcome 2 barriers that threatened it. 1. The wild animal that wants to eat me and 2. The homeowner who acted in a manor that made it more likely that it would succeed.

My actions would fall under self defense. If previously I concluded that my actions in such a scenario would be immoral and that I would be morally obligated to pay for damage that I caused to your property, I was incorrect. I failed to see that forced entry and utilizing your property to defend my life was not trespassing and theft at all since my actions are morally justified as acts of self defense.

August 17, 2013 at 2:47 pm

The fact that he could have prevented it doesn’t make him responsible

I’m really struggling with this particular statement. There was a time when I would have agreed but right now it doesn’t seem true to me.

Thanks for the good conversation. Ive done my best to logically defend a position. I’m sure if I were to reflect on everything that ive said there would be things that I would change. These are tough issues that man has wrested with for centuries. As of now I’m sticking with my assertion that it is never moral to steal although the ramifications of this view are not entirely clear to me at this time, especially in the difficult scenarios you have brought up. It has been a healthy mental exercise nonetheless.

August 17, 2013 at 3:38 pm

If the Bush administration had prior specific knowledge of the 9-11 attacks should they be held accountable for doing nothing to prevent it?

August 17, 2013 at 9:57 pm

“Its a violation of the right to life when one is present in a life or death situation and has the resources to save a life but chooses to do nothing.”

No, there is no right to life.

“I failed to see that forced entry and utilizing your property to defend my life was not trespassing and theft at all since my actions are morally justified as acts of self defense.”

No, forced entry and using peoples’ property without their consent is trespassing and theft, not self-defense.

Your claim that you have the right to break into someone’s house because it’s necessary to save your life from the animal is incoherent. This claim can be generalized as follows: one has the right to use a resource (regardless of the owner of the resource) if using it is necessary to save one’s life. To see why this claim is incoherent, consider this similar scenario in which there are two people who require the use of the same resource to save their lives:

Suppose Albert and Ben both have a fatal Disease X that will kill them in a month if they do nothing. The one known cure of Disease X is to eat Pill X. There is only one Pill X in existence and nobody knows how to make more of them. Albert and Ben are sitting across from one another at a table. Pill X is sitting on the center of the table between them. Now, regardless of who we suppose the owner of the Pill X to be in this scenario, this much is clear: your claim that both Albert and Ben have a right to use Pill X to save their lives is false, since these two rights come into conflict with each other.

If you don’t realize why it matters that the rights conflict with each other, suppose that Albert picks up the pill and starts to put it into his mouth. You are claiming that he has the right to do this since it’s necessary that he eat the pill to save his life. The implication of this would be that anyone who uses force against Albert to prevent him from exercising his right to eat the pill would be an aggressor. Thus, if Ben used force against Albert to prevent him from eating the pill he would be committing aggression. Yet, you also claim that Ben has the right to eat the pill, since using the pill is the only way he can save his life. You cannot simultaneously claim that it’s aggression for Ben to take the pill from Albert and that Ben has the right to take the pill from Albert. You’d be committing a contradiction.

“Thanks for the good conversation. Ive done my best to logically defend a position. I’m sure if I were to reflect on everything that ive said there would be things that I would change. These are tough issues that man has wrested with for centuries. As of now I’m sticking with my assertion that it is never moral to steal although the ramifications of this view are not entirely clear to me at this time, especially in the difficult scenarios you have brought up. It has been a healthy mental exercise nonetheless.”

I had hoped that if I stuck with you to try to help you give up your dogmatic belief you would have, but it appears instead that you have chosen to bite the bullet. Interesting.

October 4, 2013 at 3:25 pm

Regarding schools, the results of anarchy are amazingly good; even a consequentialist must ask why we allow the State to use force. First off, for those who do succeed in government schools, it is hard to give credit to the government, when the strongest predictors of success in government schools are things like “parental involvement” (at home, not in the school) and “how many bookcases are at home” and “did the child learn to read and do basic math before starting school?” With research results like this, one starts to wonder if much of the heavy lifting is taking place at home, not in the schools.

We actually have an experiment in school-free education; we call it home schooling. About 2.5 million American children learn at home, not at school, and the results of standardized tests show that their average is at the 85th percentile – and many do far, far better. Some start college at the ages of 12 or 14, rather than 18.

Nor is this the only option. James Tooley discovered vast hidden networks of thousands of parent-funded government-free schools in the poorest provinces of India, Africa, China, and S. America. He and his researchers tested 32,000 students and found that these schools are better at teaching math and English than the competing government schools. Their costs of operations are also lower.

I have not even mentioned the conflict of interest – government schools tend to teach government myths. Joel Spring, author of Pedagogies of Globalization: The Rise of the Educational Security State, concludes that the main purpose of government schools is to protect the interests of the government itself. John Taylor Gatto, author of the Underground History of American Education, comes to similar conclusions. Such schools may be worth less than nothing.

October 4, 2013 at 8:57 pm

Hi Terry,

Thanks for the great information. (I added Amazon links to the books you mentioned.) I agree that the case for government schools fails even by a consequentialist standard that ignores the immorality of the act of coercing people to fund or attend a school against their will. It’s unfortunate that most people assume government schools are good and necessary merely because they have existed in western societies for the last several decades. It’s a typical case of status quo bias.

Both of my sisters are currently majoring in education in college and plan to work as teachers at government schools in the future. I have no doubt that they will both be much-better-than-average teachers, but even given this I still don’t think they should work in government schools because:

(1) their skills could be put to better use if they worked in the voluntary sector (they could help more children learn more) and

(2) some of their pay will be unjustly taken from others against their will using the threat of punishment.

I have not yet discussed these points with them, largely because I don’t like trying to change peoples’ views who aren’t open to changing their views. It can be a very unpleasant experience to tell someone intelligent my views and then see them react with blatantly fallacious and emotional arguments. I’m often tempted to point out what’s wrong with their reasoning, but usually whenever I do they get upset since they don’t want to hear that their fundamental beliefs are wrong. Basically, I unavoidably cause them to feel cognitive dissonance, which is no fun for them or me—who wants to make people feel discomfort? This is why I almost always stick to internet discussions with people who are open to changing their views.

However, perhaps I could tell my sisters my views and the reasons I hold them without any intent to change their minds. If they don’t want to think about the issues I raise, then that’s fine. Perhaps in this way I could possibly lead them to start questioning their beliefs without the risk of causing them to feel discomfort and become emotional.

Will Kiely

Pingback: “The Problem of Political Authority” by Professor Michael Huemer | Peace Requires Anarchy

Pingback: What is Huemerian Anarchist Libertarianism? | WilliamKiely.Liberty.me

May 9, 2017 at 8:43 am

Yes, these are vampire tales as they are meant to be written. Don't miss Eri&3#0n9;s tale in this compendium that will absolutely blow you away. If there is one book to read this year, it's Their Dark Masters. I guarantee it.